How the Proposed Border Adjustment Tax Would Affect Dumping Margins

by Andrew Szamosszegi, Charles Anderson, and Travis Pope

This post is the first in a two-part series on the effect of the proposed Border Adjustment Tax on trade remedy investigations in the United States. The first post assesses the impact on the calculation of anti-dumping duty rates at the Department of Commerce. For a look at the effect on injury investigations at the U.S. International Trade Commission, please see the second post.

As part of its proposed corporate tax reform, the Republican House Ways and Means Committee has adopted a border adjustment tax (BAT) that would dramatically alter the taxation of exports and imports. While President Trump has criticized the plan as “too complicated,” he offered vague support for the concept in his recent address before a joint session of Congress. The proposed tax plan has the potential to influence U.S. trade remedy investigations, which depend on the prices at which imported products are sold in the U.S. market and home market prices. This blog examines how the BAT might affect one aspect of U.S. antidumping investigations: the calculation of dumping margins by the Department of Commerce.[1]

What is a BAT?

The BAT is just one aspect of the tax plan developed by House Republicans that would replace the current corporate tax rate of 35 percent with a cash flow tax of 20 percent. The proposed tax would be “destination-based,” meaning that taxes are imposed based on the location of the final sale, as opposed to the current U.S. system based on the product’s origin. Cash flows from exports are exempt from the new tax, while expenditures on imports would be non-deductible.

The table below illustrates the effect of the BAT on the costs and revenues of domestically produced goods, imports, and exports after accounting for taxes. With fixed exchange rates and other simplifying assumptions, the after-tax cost of $100 of a domestically produced good is only $80, whereas an equivalent imported good is $100. At the same time, the revenue received by an exporter of the same good is the full $100 while the same good sold domestically would generate only $80 in after-tax revenue.

Table 1: Basic Illustration of the BAT

Relative to the current system, a domestic firm would be incentivized to purchase more domestic inputs and a seller would be incentivized to export rather than sell to the U.S. market. At first glance, both changes would appear to promote U.S. production and improve the U.S. trade balance. There is considerable uncertainty, however, regarding the practical trade flow consequences of such a tax regime, if it were to be actually implemented.

How Would a BAT Impact Trade Flows?

As an initial matter, many of the largest U.S. trade partners, including China, the European Union, and Mexico, already exempt exports as a part of their value added tax (VAT) systems. The cost of U.S. imports from VAT countries selling for $100 in those markets would be $80 in the United States and have an advantage over U.S.-produced goods selling for $100 here. Reform advocates (for example, here and here) argue that a VAT distorts trade and a cash flow tax with a border adjustment would not be any different. However, both of these points are debatable: many economists believe a VAT does not distort trade flows, and the distinctions between a VAT and a BAT are relevant. It is also unclear if the BAT conforms to WTO standards. This blog does not attempt to resolve these issues here, but in fairness to the reform advocates, their argument is not for the United States to get a leg up on the competition, but to level the playing field. Whether or not that is actually the case is an open question.

Perhaps the most important – and least understood – effect of the proposed BAT is its impact on currency exchange rates. In theory, the imposition of the BAT should place upward pressure on the U.S. dollar, causing an appreciation which would neutralize the predicted financial benefit to U.S. exporters and detriment to U.S. importers. If the exchange rate adjustment was sufficiently large, the BAT would have no impact on the U.S. trade balance at all. The appreciation in the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies would offset the border adjustments’ advantage to exports and disadvantage to imports. However, the magnitude and speed of the exchange rates adjustment is a matter of considerable debate among economists.

In a recent policy brief, Gary Hufbauer and Zhiyao Lu of the Peterson Institute for International Economics review the literature on the exchange rate and trade effects of border adjustments. They summarize the methods and results of ten studies from economists and investment banks over the past fifteen years. Studies can generally be placed in two groups: 1) those that simply assume a complete exchange rate offset; and 2) those that empirically test the degree and timeliness of the exchange rate adjustment, and find that the offset would be incomplete and/or slow.

While the findings of the latter group seem more plausible, it is noteworthy that both groups of studies imply at least some appreciation is likely if the United States adopts a BAT. Below we examine how a stronger dollar is likely to affect antidumping duty rates.

Impact on Trade Remedy Investigations

It is important to note that the border tax adjustment regime would not generate a new downward adjustment to U.S. prices for imports. The BAT as currently envisioned taxes imports and domestic inputs differently; however, the tax is actually assessed at the time of the sale of the final product. The sale to the first unrelated U.S. purchaser (the basis for the antidumping calculation) will be exclusive of the BAT. Thus, the biggest impact on potential duties lies in the effect of the BAT on currency movements.

Having stated the above caveats, the studies reviewed by the Peterson Institute suggest that the imposition of the BAT should lead to some appreciation of the U.S. dollar, especially in the long run. While one cannot be certain of the magnitude and timing of the adjustment, a sustained appreciation in the U.S. dollar would have important consequences for U.S. trade remedy investigations, in particular the calculation of the dumping margin.

In antidumping investigations, the Department of Commerce is charged with assessing the degree to which the subject product is dumped in the U.S. market. The U.S. Price, the price of a country’s exports to the United States, is compared to a product’s Normal Value. In cases involving imports from market economies, Normal Value is simply the sales price in the home market. In cases involving “non-market economies,” (NMEs) primarily China and Vietnam, Normal Value is calculated based on imported unit values in a surrogate country, typically Thailand. [2]

The potential impact of a BAT on the antidumping duty rate is best viewed through the margin rate formula:[3]

Margin Rate = (Normal Value – US Price) / US Price

Where Normal Value is the observed or estimated price of the product in the home market and US Price is the price of the exported product sold in the United States. As can be seen from the formula, an increase in the U.S. Price holding Normal Value constant reduces the antidumping rate by reducing the numerator and increasing the denominator. In contrast, an increase in Normal Value holding the U.S. Price constant increases the rate by increasing the numerator.

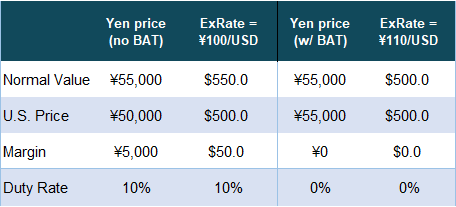

A stronger dollar means a lower duty rate. For example, say a Japanese producer of hot rolled steel price discriminates by exporting steel to the United States at ¥5,000 per ton and selling the same steel in Japan for ¥5,500 per ton. If Japanese steel is under a U.S. antidumping order and the exchange rate is ¥100 per dollar, the antidumping margin is 10 percent, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Impact of a Hypothetical Dollar Appreciation on the Margin of a Japanese Steel Producer

Assuming that the BAT results in a 10 percent dollar appreciation to ¥110 per dollar, Normal Value (i.e., the price in Japan) declines to $500 per ton. Thus, the exporter no longer needs to price discriminate in order to compete in the U.S. market at $500 per ton. As shown in the table above, the Japanese producer can raise the yen price of its exports to ¥55,000 per ton and the duty rate disappears.

However, basic economics suggests that second order effects may influence the extent of the decline. Although inputs purchased in Japan are now cheaper in dollar terms, the marginal cost of production is likely to increase in yen terms because dollar appreciation increases the cost of imported inputs purchased in dollars. The resulting upward shift in the supply curve will increase the home market price (Normal Value). While it is unclear from this example what the margin will be, if the Japanese producer wishes to maintain its $500 per ton price in the U.S. market, it is clear that the duty rate following a BAT-induced appreciation is likely to be less than 10 percent.

The implication of this example is that the impact of a stronger dollar on the Normal Value and U.S. Price will vary by national and industry characteristics:

· The change in the dollar exchange rate for a given subject country or, in the case of non-market economies, the surrogate country

· The subsequent adjustments in the subject country’s currency relative to other currencies

· Whether the subject country is a market economy or a non-market economy

· The industry and market structures in the subject/surrogate country and the United States

· The ultimate form of the BAT

Exchange Rates in the Subject/Surrogate Countries Relative to the Dollar

The discussion above assumed a general strengthening of the dollar against global currencies, but exchange rate effects for particular currencies will be heterogeneous. Countries with floating exchange rate regimes would see a weakened currency in line with the market. Countries with fixed exchange rates pegged to the dollar would face a choice of: a) using their foreign reserves to push against depreciation, b) accepting a one-off adjustment and pegging to the dollar at a new level, or c) some combination of the two. Thus, the variety in exchange rate regimes will lead to different outcomes among the currencies of U.S. trading partners, and therefore different impacts on duty rates.

Exchange Rates in the Subject Country Relative to Its Trading Partners

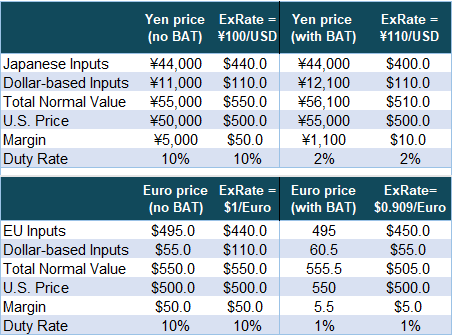

The heterogeneous exchange rate effects of a BAT imply that cross rates among U.S. trading partners will also vary. These exchange rate movements are important because countries vary in their sources of inputs for products eventually sold to the U.S. market. If these inputs become cheaper in dollar terms, the U.S. Price in the margin calculation may decrease at the same time Normal Value decreases, mitigating the effect on the dumping margin, as described above. For example, compare Japan and the European Union. [4] While both the yen and euro are allowed to float, the mix of exchange rate regimes in their major import partners are different. Japan’s largest source of imports is China. If China maintains its value with respect to the dollar, the cost of these inputs will remain constant in dollar terms and increase in yen terms. In contrast, European countries’ largest trading partners are other European countries that use the euro. The price of European inputs would therefore mostly decrease in dollar terms and remain constant in terms of the euro, thereby limiting the decrease in the dumping margin. In the table below, the dollar appreciates by 10 percent versus the yen and the euro. However, the Japanese steel producer is assumed to purchase 20 percent of its inputs in dollars or currencies linked to the dollar, while the EU exporter purchases only 10 percent of its inputs in dollars. The margins and duty rates of both exporters decrease, but the EU exporters’ margin declines by a greater amount.

Table 3: The BAT’s Varying Effect on Trade Partners

Market vs. Non-Market Economies

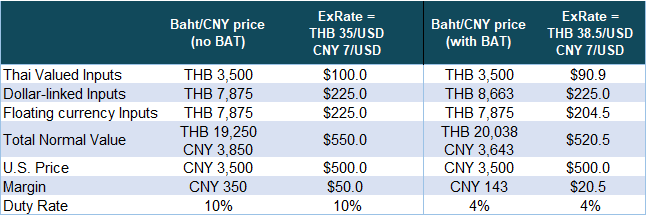

For non-market economies (NME), namely China and Vietnam, the Normal Value is calculated based on a surrogate country (typically Thailand), while the U.S. Price is calculated the same way as market economies.[5] Both China and Vietnam have exchange rates linked to the U.S. dollar, while the Thai baht is allowed to float.[6] For an NME like China, this means that the margin will be influenced by the impact of dollar appreciation on Thai-sourced inputs (wages and electricity) and Thai imports. As shown in the table below, dollar appreciation would reduce the value of Thai-based surrogate values. This would reduce Normal Value and the margin. For imports from the United States and countries linked to the dollar, the cost in baht would rise, but the depreciation of the baht leaves the cost unchanged in dollar terms. For imports from countries with floating currencies, any dollar appreciation resulting from a BAT would reduce the dollar value of the inputs and therefore reduce Normal Value and the margin. Assuming that China manages an appreciation that matches that of the dollar and holds the U.S. price at $500, the antidumping duty rate declines from 10 percent to 4.1 percent.

Table 4: The Impact of the BAT on Constructed Value for Non-Market Economies

Market Structure and Pass Through

Market structure in the home and U.S. markets will also play a role in how the BAT influences the margin. If the home market is competitive (no producer’s output decision can influence the home market price), then Normal Value will not change in terms of the home currency. This is the case in Table 2. If the exporter has market power in the home market (i.e., faces a downward sloping demand curve), the increase in marginal cost may lead to an increase in the home market price that would offset some of the decline in the margin caused by the appreciation, similar to the dynamic in Table 3.

Producers may also vary in the extent to which they pass on the benefit of dollar appreciation to U.S. consumers in the form of lower prices. In each of the scenarios above, the producer is assumed to keep the U.S. price in dollars unchanged. If increasing its U.S. market share is important to the Japanese exporter in Table 2, it may decide to pass on the benefit of the weaker yen to U.S. consumers by reducing the U.S. price. This would have the effect of increasing the with-BAT margin above the level shown in Table 2.

Typically, the degree of exchange rate pass through depends on the nature of the product and industry. If price is the most important factor in a consumer’s purchasing decision, such as for commodity products, the Japanese producer will likely choose to lower prices and increase sales. If other factors drive purchasing decisions, the firm would choose to maintain prices. This would likely be the case for differentiated products such as high-end branded goods.

The degree of pass through would also be influenced by the BAT itself. With the loss of deductibility, imports would be relatively less attractive to U.S. businesses. In price competitive markets, the hypothetical Japanese producer would likely need to reduce the U.S. price or risk losing sales to existing customers. This price reduction would partially offset the decrease in the margin caused by the stronger dollar.

The Form of the BAT, as Implemented

Finally, it should be noted that the ultimate form of the BAT will have important consequences. At the time of this writing, the proposed cash flow tax would make domestic labor deductible while foreign labor would not be deductible. This is a critical distinction from the value added taxes employed by other countries, and would influence the anticipated trade and exchange rate effects discussed above.

Conclusion

As a technical matter, if the BAT does increase the value of the dollar, existing antidumping duties are likely to decline. However, the magnitude of that decline depends on a number of factors, including the extent of the appreciation, the share of production inputs from countries with currencies linked to the dollar, market structure, and pass through.

At the time of this writing, the BAT was facing significant push back and seemed unlikely to become law, at least in its current form. But other types of tax reform, including the VAT, that rely on border adjustments also may lead to dollar appreciation, which would tend to reduce dumping margins.

Notes

[1] An upcoming blog will assess the potential impact of the BAT on the injury phase of antidumping investigations at the U.S. International Trade Commission.

[2] The calculation of the dumping margin should not be confused with the underselling analysis conducted by the International Trade Commission in the injury phase of trade remedy investigations. Where the dumping margin compares the price of U.S. imports to the price in a foreign country, the ITC’s underselling analysis compares the U.S. price of the domestic product to the U.S. price of the imported product. A BAT and resulting dollar appreciation would also affect the results of the underselling analysis, but in different ways.

[3] This formula simplifies the margin calculation by assuming one product. In practice, the margin is calculated as a weighted average based on the U.S. prices (also known as the export price), normal values, and quantities of multiple products.

[4] This example assumes that both Japan and the EU increase home market prices to reflect increases in marginal costs. By assumption, 20 percent of Japan’s inputs are tied to the dollar while only 10 percent of EU inputs are tied to the dollar.

[5] “Market Economy” and “Non-Market Economy” status are classifications determined by the Department of Commerce for the purpose of the dumping margin methodology. While other countries such as Cuba and North Korea could potentially be treated as non-market economies, only China and Vietnam have recent trade remedy investigations.

[6] Inputs imported from countries with floating exchange rates will get cheaper, but this is true of other countries as well