How the Proposed BAT Would Affect USITC Investigations

by Andrew Szamosszegi, Charles Anderson, and Travis Pope

In a recent post, we explored the impact of a proposed Border Adjustment Tax on the dumping margin calculated by the Department of Commerce in trade remedy investigations. In this installment, we explore the impact of the BAT on injury investigations at the U.S. International Trade Commission. For a more complete discussion of the BAT and its potential impacts on global trade flows and exchange rates, please see the first post.

The Border Adjustment Tax (BAT) proposed in the House Ways & Means Committee would have significant implications for the injury phase of trade remedy investigations conducted by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC).[1] The BAT would have two primary effects related to USITC investigations. First, it would raise the after-tax cost of imports relative to domestically produced goods. Second, the BAT is likely to cause an appreciation of the U.S. dollar, though economists differ on the degree of the exchange rate adjustment. Both of these changes would create confounding factors for the typical assessments made by the USITC: price effects of subject imports, quantity effects of subject imports, and financial effects on the domestic industry.

In terms of USITC investigations, the BAT’s complications can be placed in two categories. First, some measures traditionally collected and relied on by the USITC in its injury assessments should not be fundamentally altered; however, a one-time change in the corporate tax regime will create a one-time change in important trend lines. Unless the USITC adjusts its analysis to account for these one-time changes, the switch from a conventional corporate income tax to BAT could skew the outcomes. USITC investigations and reviews are conducted over three-year periods of investigation (“POI”) and five-year periods of review (“POR”), respectively. For investigations and reviews where the BAT policy change occurs in the middle of the POI or POR, the USITC will need to account for breaks in the data owing to different accounting standards applied in different years. Second, some traditional USITC “indicia” of injury may need to be adjusted both in the near and long term. Examples include the underselling analysis and U.S. industry profitability assessments.

Price Effects

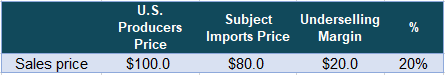

A BAT is likely to affect the Commission’s analysis of price effects. When the Commission examines price effects of the subject imports, it considers the extent to which the subject imports are priced below sales by the domestic industry at the same level of trade. As set forth below in the simple example, if a domestic producer sells its product for $100 and the importer sells the subject merchandise for $80, the underselling margin is 20 percent.

The Commission also considers whether the lower priced imports depressed the prices of the domestic like product or prevented domestic producers from increasing prices in response to higher costs.

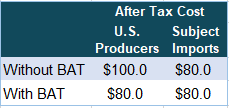

Since the BAT does not directly affect the price of the subject import, a BAT would not change the margin of underselling. What the BAT does, however, is complicate the interpretation of whether the magnitude of underselling is significant. The impact of the BAT is indirect. As shown in the table below, an underselling margin of 20 percent without the BAT means that purchasers of the dumped imports save $20 per unit. With a BAT, purchases of the subject imports are not deductible. The purchaser saves $20 per unit on the domestic product because it is deductible, but saves $0 dollars on the subject import. Thus, with a BAT the net costs of the domestic product and the subject import are both $80, despite the fact that the underselling margin is 20 percent.

This wedge between the sales price and net cost to the purchaser may require the Commission to recalibrate what it deems to be significant underselling. A 20 percent margin is normally considered significant, but with the BAT as currently envisioned, a 20 percent margin would provide no competitive benefit to the dumped merchandise. Alternatively, the Commission may have to adjust the underselling analysis for differential tax effects.

As discussed in the previous post, economists believe some appreciation of the dollar is likely if the United States imposes a BAT. [2] Dollar appreciation could potentially lead to even larger margins of underselling, depending on the currency of the exporting country and the extent to which the dollar’s appreciation is passed through to the U.S. price. If the dollar appreciates to offset the 20 percent BAT, foreign exporters could reduce their prices in U.S. dollars while earning the same or more revenues in their home currencies. For an export from Japan valued at ¥8,000, the U.S. price is $80 at an exchange rate of ¥100/$ and $66.67 at an exchange rate of ¥120/$. As the table below shows, the underselling margin for exporters from countries who pass through none of the change in the value of the dollar and exporters from countries whose currencies are linked to the dollar will remain 20 percent. As firms pass through changes in the value of the dollar by reducing the U.S. price, the margin of underselling increases.

This analysis suggests that the BAT currently being considered is likely to have two effects on the Commission’s underselling analysis. First, the Commission will either have to adjust for differential tax effects, or reassess what it deems to be a significant magnitude of underselling because the non-deductibility of imports dilutes the competitive effects of underselling. Second, to the extent that the BAT leads to dollar appreciation, the underselling margins for some exporters are likely to increase. Taken together, these effects suggest that the magnitude of underselling could become more volatile — especially during the transition period, when prices and exchange rates are adjusting for the change in tax regime — and thus a less reliable barometer of the subject imports’ price effects on the domestic industry.

Quantity Effects

The BAT would make the exports of U.S. producers tax-deductible. If the exchange rate adjustments do not result in a complete offset of the BAT effect, U.S. industries would be incentivized to increase exports relative to shipments to the U.S. market. The degree to which U.S. industries shift to an export focus will vary significantly by industry and firm, but such shifts could create distortions in the USITC’s conventional approach to assessing the effect of subject imports.

One standard assessment made by the USITC in injury investigations is whether the subject imports had an effect on the domestic industry’s volume of production and U.S. shipments. For example, if subject imports from a given country increase over the period of investigation and the domestic industry’s U.S. shipments decrease, it would appear, at least at first glance, that the subject imports are causing the domestic industry to lose out on sales volume.

The issue created by the BAT, however, is that these same trends would be present in an industry where domestic producers have shifted to an export focus, even if subject imports were having no injurious effect. To the contrary, a greater volume of subject imports might be demanded by the U.S. market precisely because there is less domestic supply to go around.

While the USITC already collects data on exports shipments in its investigations and sunset reviews, any changes in domestic industry behavior would complicate the Commission’s task, especially if the domestic industry’s capacity utilization is high.

Financials Effects

Nominally, the BAT will not affect the financial data collected from domestic producers because all financial measures used by the USITC (gross profit, operating profit, net income) are measured before taxes. Thus, the change in tax policy will not affect the standard measures of profitability.

However, the increased incentives to export may create significant changes in the structure of certain industries. For example, firms may shift their focus from selling a (relatively) undifferentiated product in the United States to exporting high value added products, resulting in lower domestic sales that coincide with increased after-tax profitability. Overall, U.S. industries may appear to be less profitable at the operating level; however, the change may be attributable to a shift from domestic to export shipments, in order to earn the higher after-tax profits on sales in export markets. To isolate such factors in its assessment of financial performance, the Commission may wish to begin collecting financial data separately for U.S. producer domestic and export sales. This has been done in select cases in the past, such as in Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel from Germany, Japan, and Poland in 2014. Petitioners who are major exporters or who increase their export activities due to the BAT should be prepared to supply this information.

Another possible consequence of the BAT is that it would result in one-time increases in the pre-tax cost of goods sold, as U.S. producers shift from imported inputs to more expensive domestic inputs that generate tax deductions below the operating profit level. Such a shift would make it more difficult for the Commission to determine whether price suppression is the result of the subject imports or a consequence of the BAT. One way to isolate such financial effects would be to split domestically-sourced and imported inputs in the cost of goods sold line on the USITC’s traditional financial results template.

Alternatively, the USITC may want to place more emphasis on after-tax profitability in assessing domestic industry trends. Traditionally, the USITC has avoided after tax profitability measurements because they are subject to manipulation and do not make for apples-to-apples comparisons across firms or years. However, the cash flow tax currently under consideration could eliminate much of the underlying differences in tax outcomes. According to its proponents, the new system is supposed to make taxation simpler and more uniform. If this is in fact the case, the rationale for eschewing after-tax profitability could be greatly mitigated if deductions related to capital expenditures are excluded.

Conclusion

The proposed BAT would influence industry investigations at the USITC in several ways, some of which would cause the Commission to request additional data and possibly revise its traditional analytical methods. The analysis of volume effects would require the Commission to consider whether any decline in domestic industry volume and market share is due to incentives that favor export sales over domestic sales. The analysis of price effects would need to take into account that the BAT creates a wedge between the sales price of domestically produced goods and their after-tax cost to purchasers. If the cash flow tax is 20 percent and only domestic purchases are deductible, then an underselling margin of 20 percent provides no competitive benefit to subject imports used in the production process. On the other hand, if the dollar appreciates after the imposition of the BAT, underselling margins may rise as the competitiveness of imports increases. The BAT would also influence the Commission’s impact analysis because changes in pre-tax profitability may reflect a shift to higher margin export sales, thereby masking adverse effects of subject imports. The Commission would have an interest in collecting financial data that isolates the injurious effects of imports from more profitable export sales.

Notes

[1] The USITC is charged with assessing whether a domestic industry in the United States has been injured, or is under threat of being injured, by imports of a particular product from a subject country or group of subject countries.

[2] Some economists believe that the U.S. dollar will appreciate to neutralize the effect of the BAT on trade flows. Other economists believe that the appreciation, if it occurs, would be unpredictable in magnitude and timing. Hufbauer and Lu of the Peterson Institute for International Economics provide a review of the literature here.