Three Reasons Why the U.S. Should Care About Brexit

Authors: Chi Kim and Laura Delgado.

The referendum for the British exit from the European Union (EU), or ‘Brexit’, was passed on June 23, 2016. Reactions to Brexit underlined a great deal of uncertainty about Europe’s political and economic future. In the United Kingdom, new Prime Minister Theresa May and her Conservative Party cabinet now face the daunting task of re-establishing the United Kingdom’s political and economic partnerships. The EU must renegotiate its relationship with the UK, while remaining firm on political positions that are unpopular among many British voters. Beyond the political sphere, the British economy endured Brexit’s initial shocks, but its economic future depends heavily on Prime Minister May’s success with economic partnerships. Many are not optimistic; the International Monetary Fund lowered estimates of Britain’s GDP growth forecast for 2017 by 0.9 percentage points to 1.3 percent, while many European countries were revised downward as well.

Although Europe remains the epicenter of Brexit’s economic and political instability, the United States is not insulated from the shocks felt across the water. In a meeting with the Senate Banking Committee following Brexit, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen commented that the Fed is carefully monitoring global conditions as the Brexit vote could have “significant economic repercussions” on the United States. Although this started as a European issue, Americans should be aware of Brexit’s economic effects. To help, we summarized some of the anticipated effects of Brexit on the U.S. economy and trade outlook.

1. Current and continuing instability in Europe, an important U.S. trading partner

The European Union (EU) is a significant trade partner for the United States, and will still remain so after Brexit. In 2015, American exports of goods to the EU totaled $273 billion and goods imports totaled $426 billion. Together, the EU ranks as the 2nd largest export market and supplier of imports to the United States. The United Kingdom accounted for 12 percent of exports to the EU and 10 percent of imports from the EU in 2015.

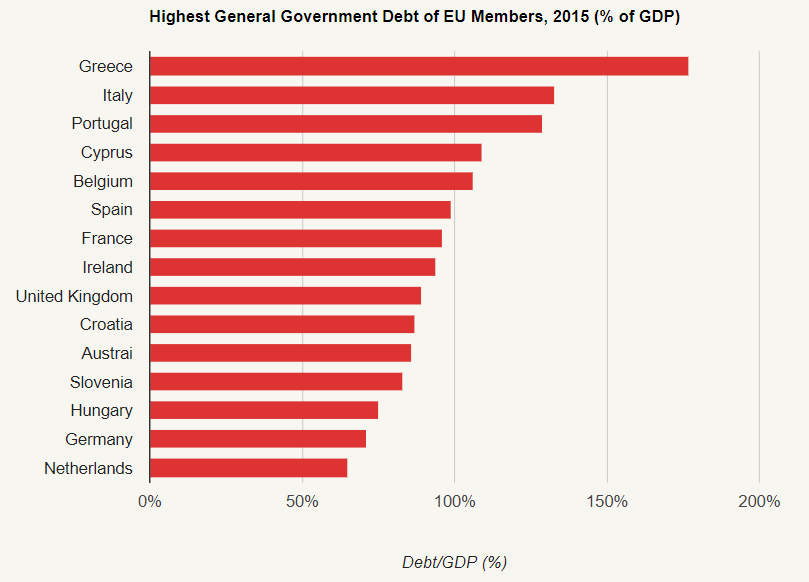

Economically, Brexit adds uncertainty and volatility to an already weak European economy. In 2015, overall GDP growth in the EU was only 1.7 percent. The main restraints on growth are the lingering effects from the most recent financial and economic crises, including high levels of debt and unemployment. In 2015, EU member states had a gross public debt around 93 percent of the GDP, and unemployment at around 11 percent. Weak investment, unfavorable business environments, and public administration inefficiencies are among other issues that require structural reform and economic policy. The United Kingdom leaving the EU, in its time of slow recovery, will further delay economic stability and consistent growth.

Source: Eurostat

Britain is not the only country considering an exit from the EU. Riding the tailwinds created by Britain, Italy’s most popular political party, the populist Five Star Party, is in favor of exiting the European Union in a referendum on constitutional reform in October. The Guardian’s Stephanie Kirchgaessner reports that “the referendum is increasingly being seen as a way for Italians to air their general discontent with the establishment.” If the referendum results favorably for the Five Star Party, “Quitaly” could very well be the next major exit for the EU. Other populist movements criticizing the EU are gaining traction in France, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

2. Effects on the Exchange Rate and Wall Street

The political instability in Europe following the Brexit vote creates negative externalities for all European economies and their international trade partners. Brexit alone will not drag the U.S. economy into a recession, but a Brexit-induced recession in the UK and continued stagnation in the EU will diminish global growth prospects and influence U.S. economic performance.

The Brexit vote initially caused skittish investors to pull out of European markets and pour into the United States. Correspondingly, the pound dropped significantly, reaching its lowest point relative to the dollar since 1985. More than two months later, the pound has not recovered and is currently trading at 13 percent below its value against the dollar in January of this year.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The appreciation of the dollar against the pound and euro suppresses global demand for U.S. exports, while increasing the competitiveness of imports compared to companies that produce in the U.S. As a result, many economists are changing their projections for global and domestic growth. The International Monetary Fund cut 2016 GDP growth projections for the United States by -0.2 percentage points to 2.2 percent. Political and economic uncertainties are the driving force behind these more pessimistic projections. The combination of a stronger dollar and weaker global growth, particularly in the economies of our major trading partners, will be a drag on U.S. exports, and many domestic industries.

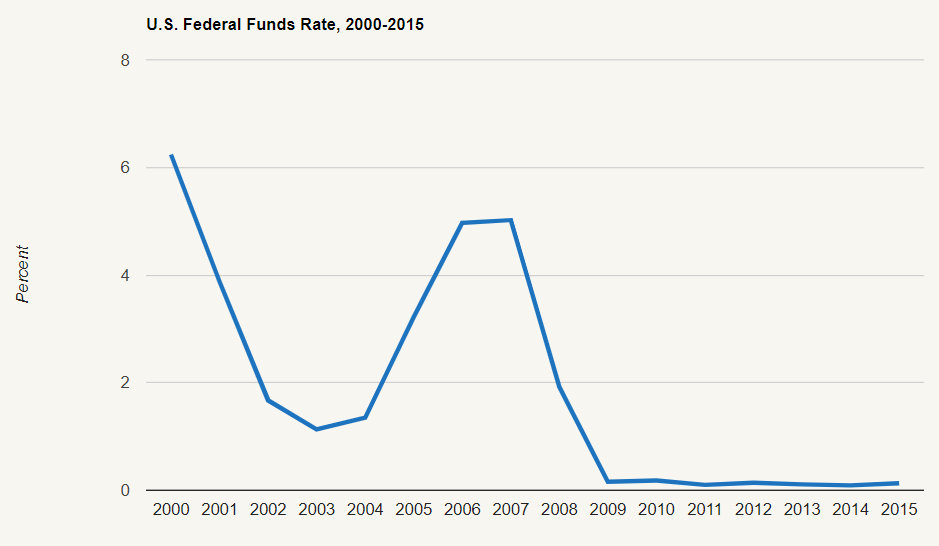

The Federal Reserve has implemented special measures to deal with Brexit, providing dollar swap lines and short-term credit lines to cover currency shortages overseas. Brexit also affects the Fed’s decision on whether to raise the federal funds rate. During the July 26-27 policy meeting, the Federal Reserve iterated that they would be “carefully monitoring developments in global financial markets, in cooperation with other central banks, following the results of the U.K. referendum.” Considering this, it is possible the rate hike will not occur until December, or even in 2017.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

3. A UK and U.S. Trade Deal?

Since the Brexit, several U.S. politicians have floated the idea of a US-UK free trade agreement (FTA). Republicans such as House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wi.) and Senator Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.). However, President Obama made clear that an FTA with the UK would move to “the back of the queue.” Politics aside, the question is whether a U.S.-UK FTA makes economic sense.

If the U.S. and UK ever do negotiate a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the typical points made by FTA critics would be far less potent. Critics of FTAs often cite potential problems including enlarging the trade deficit, foreign currency manipulation, and loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs due to competition from low-wage workers. However, U.S. trade with the UK is relatively balanced, UK wages are comparable to U.S. wages, and nobody is accusing the UK of currency manipulation. Considering these points, a U.S.-UK FTA would probably be less controversial and easier to negotiate, compared to other recent U.S. trade deals such as the Korea-US FTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

It is possible that a U.S.-UK FTA could improve the already strong trade relationship between the UK and U.S. FTAs are designed to foster and open trade flows; enhance competitiveness of a country’s exports to its trading partner; eliminate tariffs and other barriers that impeded the flow of goods and services; and build framework that protects trade-related issues (i.e. intellectual property, environmental and labor protections, and other legal issues). An FTA with the UK could make U.S. products even more attractive. The UK already buys billions of dollars in planes, helicopters, spacecraft, refined petroleum, medical products, and a wide variety of other American goods. Although the U.S. has run trade deficits with the UK since 2011, bilateral trade is far more balanced than U.S. trade with many other countries. For 2016 so far, the U.S. is running a trade surplus with the UK, according to data from the Census Bureau. The trade balances for the previous 15 years are shown in the graph below, from U.S. Census Bureau data:

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

A FTA with the UK is not the only option. The U.S. could pursue a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), a Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), or a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) in lieu of a FTA with the UK. BITs, for example, help protect private investment, in order to develop market-oriented policies in partner countries, while promoting U.S. exports.

TiSAs is a trade initiative focused on fair and open trade across service sectors. Currently 23 parties are participating in TiSA, including the European Union. When the UK is no longer part of the EU, it will have to decide whether to join TiSA. From the U.S. perspective, the UK will hopefully join TiSA because the agreement benefits the U.S. through increased transparency and effective regulatory policies, such as restricting cross-border data flows that can disrupt services trade over the internet.

TIFAs provide frameworks and principles for dialogue on trade and investment. The U.S. has dozens of these treaties, with countries or regions around the world including Asia, Europe, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. Some of the important benefits of TiFAs include:

· Cooperation between parties on trade and investment

· Reduction of barriers to trade and investment, such as non-tariff barriers

· Agreement on specific trade and investment matters

· Increased trade transparency

· Increased foreign direct investments, and private sector investment.

Ultimately, even without an FTA, the UK will continue to receive most favored nation treatment (MFN) and be subject to MFN duty rates in the United States, as was the case before Brexit. Whatever the outcome of potential trade negotiations, the U.S. and UK will remain strong trade partners.

Conclusion

Brexit has exacerbated political and economic instability within the United Kingdom and in the rest of Europe. Based on recent projections, global growth is likely to suffer as well, with both positive and negative consequences for the U.S. economy. However, Brexit also presents an opportunity to enhance the special relationship between the United States and Britain. Only time will tell what type of trade deal the U.S. might achieve with the UK, how investors will behave, and where the exchange rate will go. As the British say, we’ll prepare for the worst, but hope for the best.

Notes

[1] Data comes from the Office of National Statistics, and the Office of Statistics in Scotland.