Reviewing the 2015 Trade Numbers

Full-year 2015 trade data from the United States International Trade Commission are now available. To celebrate, we review some of the most important big-picture developments in U.S. trade from the previous year.

The graph below is a snapshot of the U.S. trade balance in 2015. The six basket categories are based on 1-digit end-use classifications used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. [1. BEA end-use codes are used in International Transactions Accounts and the National Income and Product Accounts. These data are publicly available at the U.S. International Trade Commission’s DataWeb: https://dataweb.usitc.gov. Unless stated otherwise, these data are the source for all figures in this post.] As there is significantly more shaded area below the line than above it, one can see that the United States ran a trade deficit in 2015, as it has every year since 1975.[2. Bear in mind that the graph and all data in this article are related to the U.S. trade in goods. Services, a sector in which the United States runs a trade surplus, is excluded.] Overall, the trade deficit in goods was approximately $930 billion, or 1.3 percent of gross domestic product.

The breakdown of U.S. trade surpluses and deficits is fairly simple regarding goods. The United States does well in capital- and technology-intensive industries (think high-tech metals, chemicals, and airplanes) and many agricultural products but runs a huge deficit in labor-intensive and cost-sensitive products (think of anything you can buy in WalMart).

Comparing 2014 and 2015, U.S. exports decreased by 7.9 percent while imports decreased by 4.3 percent, leading to a 1.5 percent widening of the trade deficit.[3. Annual U.S. trade balance, from USITC DataWeb, is equal to the Total FAS Value of U.S. Domestic Exports minus the Customs Value of U.S. Imports for Consumption. GDP from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Comparisons between 2014 and 2015 are in nominal terms. Longer-run annual comparisons are inflation-adjusted.] While the aggregate trade balance was relatively unchanged, the appearance of stability is driven by two underlying factors moving in opposite directions: a tremendous improvement in the balance of U.S. trade in fossil fuels, and a worsening deficit in just about everything else.

The U.S. trade deficit in Industrial Supplies and Materials: Fuels and Lubricants was cut roughly in half over the course of 2015. The shrinking deficit in this category was a function of dramatically lower energy prices decreasing the value of U.S. imports, in addition to higher export volumes from domestic petroleum producers. The U.S. export volume of crude oil and petroleum products increased by 14 percent in 2015 while the volume of imports increased by less than 2 percent, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. This sea change in U.S. energy trade has reshaped the structure of the U.S. balance of payments over the last five years. In 2011, fuels accounted for a third of the overall U.S. trade deficit. In 2015, it accounted for just 8 percent.

For products other than fossil fuels, the trade deficit widened by 13 percent compared to 2014. The year-over-year changes in the value of traded goods are shown below, broken out by type of good at the 1-digit level.

Outside of Industrial Supplies and Materials, the United States generally saw increased imports and decreased exports in 2015, particularly for consumer goods and automobiles. The short-term widening in 2015 was unsurprising and probably inevitable for two related reasons. First, the U.S. economy is growing and the balance of payments tends to worsen, all else equal, in years when consumption increases, as consumers simply have more money to spend. Because U.S. firms no longer produce many consumer products, rising expenditures on such products lead to expanding imports. In 2015, both nominal GDP and personal consumption expenditures increased by 3.4 percent.[4. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. National Income and Product Accounts Table 2.3.5: Personal Consumption Expenditures by Major Type of Product.] Second and more importantly in this context, a stronger U.S. economy combined with economic weakness throughout the globe has led to a significant strengthening of the dollar against other major currencies.[5. Although China’s economy expanded more rapidly than the U.S. economy in 2015, its imports declined by 18 percent in 2015, in dollar terms. Nominal GDP of Japan and the EU expanded by 2.4 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively in 2015 (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). Many other economies that supplied raw materials to China also experienced slower growth in 2015.]

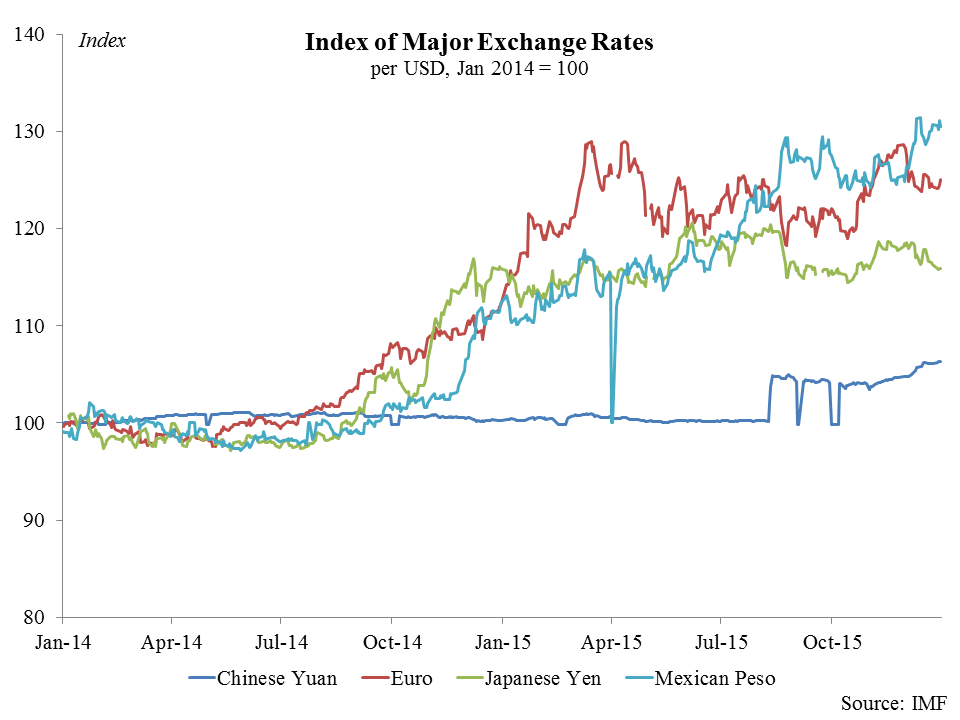

Virtually all major global currencies weakened against the dollar in 2015. Comparing the annual average of daily exchange rates from the International Monetary Fund, the Euro weakened by 20 percent against the dollar, the Japanese yen by 15 percent, and the Mexican peso by 20 percent. Each of these weakening trends started at the end of 2014 and continued through most of 2015. Even the Chinese yuan, which is effectively fixed against the dollar by the People’s Bank of China at most times, weakened by 1.4 percent against the dollar in 2015, due to the PBC’s devaluation beginning in August 2015. In all likelihood, the U.S. economy is only beginning to the feel the full effects of the weakening yuan, which occurred too late in the year to have had a significant impact on the 2015 annual numbers.

Each of these exchange rate movements has weakened the competitiveness of U.S. exports, while making imports more attractive to the U.S. consumer. These trends had a major impact on the more granular developments shown in the graph below, which breaks out the 2014-15 changes in the U.S. trade balance, by type of end-use at the 2-digit level.

2015 Winners

The only big, big winner here is in Industrial Fuels (i.e., oil), discussed above. However, two other categories saw some improvement in their balance of payments.

Capital Goods related to Transportation, which consists primarily of non-military aircraft, saw a six percent increase in the value of its exports. 2015 was a good year for airlines, and apparently that has extended to aircraft manufacturing as well.

Industrial Supplies and Materials: Agricultural Goods, which includes cotton, tobacco, and other agricultural materials used for industry, saw an $11.4 billion improvement in the balance of payments. However, this development was driven entirely by lower imports, as U.S. domestic exports also decreased.

2015 Losers

The trade deficit widened for the majority of the USITC’s 2-digit categories. In particular, two categories saw large declines on both an absolute and relative basis.

The trade deficit in Automotive Vehicles, Parts, and Engines widened by $25 billion, or 14 percent. The widening trade deficit reflects a longer term trend, as can be seen in the increasing value of automotive imports since 2010, in real terms, as shown below.

Those familiar with the recovery of the U.S. automobile industry in recent years may find this surprising. However, the trend makes more sense when one considers Mexico’s growing importance to- and integration with- the U.S. automotive sector. While U.S. automotive imports from Mexico have increased by 66 percent, in real terms, since 2010, exports to Mexico have also increased by 45 percent. These hand-in-hand increases reflect the fact that automotive supply chains straddle the U.S.-Mexican border, with parts flowing both ways in the production process. From this point of view, increasing imports would be no cause for concern-as they merely reflect increased production on both sides of the border.

However, this position has become increasingly hard to justify. U.S. automotive imports from Mexico increased by $8 billion in 2015, while exports to Mexico increased by only $300 million. There is a growing wedge in the trade balance in U.S.-Mexican automotive manufacturing- a wedge that is likely to only grow worse with the significantly depreciated peso.

Another balance of payments loser in 2015 was Agricultural Foods– a category in which the United States typically runs a trade surplus. That surplus shrank from $33 billion in 2014 to $14 billion in 2015. China, Mexico, South Korea, and Japan alone account for roughly half of that decrease. For the East Asian countries, the change can be attributed solely to the decreased value of U.S. exports, as imports were either flat or insignificant to begin with. By contrast, the agricultural foods’ trade deficit with Mexico, which nearly tripled last year, was a result of both rising imports and falling exports. Lower export values are partially a function of plummeting commodity prices, but also are a result of the strengthening dollar, as U.S. agricultural products became relatively more expensive in foreign markets while foreign agricultural products became less expensive in the U.S. market.

2016 Outlook

Policy and structural changes in the economy can and do influence the long-run outlook of the U.S. trade balance. However, short-to-medium-term changes are driven primarily by changes in exchanges rates and consumption patterns around the globe. As such, the U.S. trade balance in 2016 will likely be a function of the strength of the U.S. dollar, whether the U.S. economy continues to grow, and the economic strength, or lack thereof, in other major economies, especially China. If the dollar’s appreciating trend persists, the U.S. economy has another year of decent-to-good growth, and the economies of China, Japan, and the European Union continue to show signs of weakness, expect the U.S. trade deficit to widen further in 2016.