Yuan Shock–The Export Angle

This blog was prepared by Christine McGee and Monique Garcia.

There is a tendency to view China’s 1.9 percent devaluation of the Yuan on August 11 through the lens of the U.S. dollar. After all, the Yuan has been fixed or closely linked to the greenback for decades, and Washington has been among the most vocal critics of China’s currency policy.

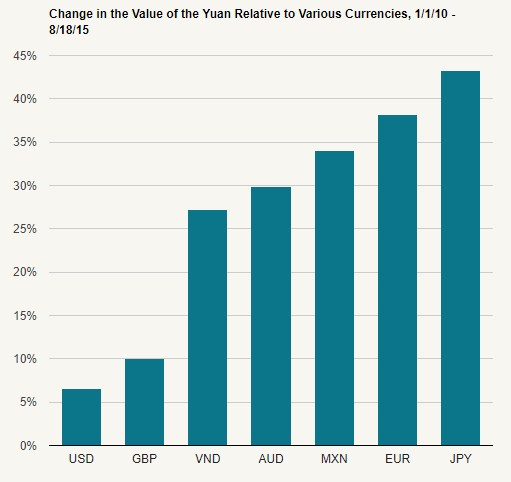

However, currency and trade data suggest that China’s devaluation has more to do with the other currencies. While the Yuan has appreciated by one third versus the dollar since China broke its link to the dollar in July 2005, the Chinese currency has appreciated even more against other currencies, as shown below.

Source: OANDA

The difference is even more pronounced if the comparison is limited to the past 5 years. Because the Yuan has remained closely tied to the U.S. dollar, the dollar’s broad appreciation has led the Yuan to appreciate substantially versus other currencies, including the Euro, the Yen, and the Australian dollar.

Source: OANDA

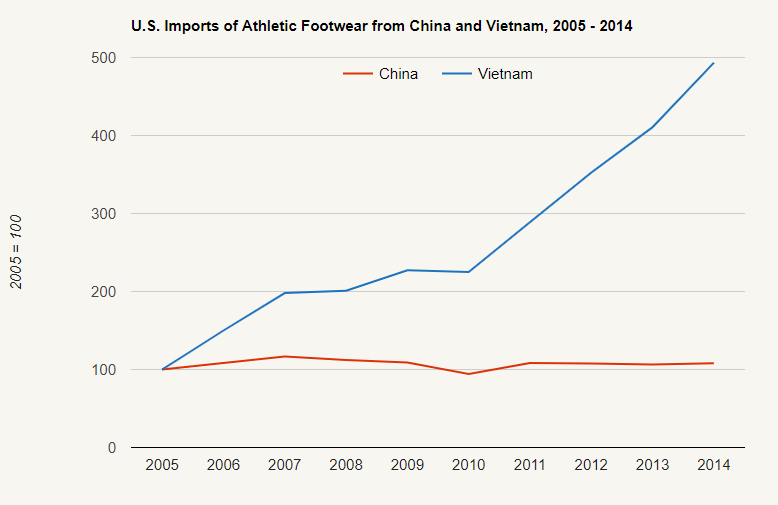

Versus some currencies, such as the Australian dollar, the strong Yuan is beneficial because it reduces the cost of imported raw materials. But against other currencies, such as the Euro, Yen, Vietnamese Dong, and the Mexican Peso, the strong Yuan harms China’s export competitiveness. For example, China has been the primary supplier of athletic footwear to the U.S. market. But as shown in the figure below, the value of U.S. imports of footwear from China has been stagnant while imports from Vietnam have been growing.

Source: USITC DataWeb

In response to China’s devaluation, Vietnam widened the Dong’s trading range. Only time will tell whether such moves continue or whether the present equilibrium remains in place.